Key points

- Central banks beyond the US are edging towards an exit from easy money. This is likely to cause bouts of volatility in shares and a rising trend in bond yields.

- However, it’s unlikely to derail the bull market in shares as any move to tightening reflects stronger growth (and profits), low inflation pressures will keep monetary tightening very gradual (as we have seen in the US) and monetary policy is a long way from being tight.

- An RBA tightening remains a long way away.

Introduction

For much of this year, there has been a surprising divergence between share and bond markets with shares up in response to improving growth and bond yields down in response to weak inflation. Some feared that either bonds or equities had it wrong, but in a way it seemed like Goldilocks all over again – not too hot (ie benign inflation) but not too cold (ie good growth). However, the past week or so has seen a sharp back up in bond yields – mainly in response to several central banks warning of an eventual tightening in monetary policy. Over the last week or so, 10 year bond yields rose 0.2-0.3% in the US, UK, Germany and Australia. This may not seem a lot but when bond yields are this low it actually is – German bond yields nearly doubled. This caused a bit of a wobble in share markets. The big question is: are we seeing a resumption of the rising trend in bond yields that got underway last year and what does this mean for yield sensitive investments and shares? Since central banks are critical in all of this we’ll start there.

Central banks turn a (little) bit more hawkish

The action over the last week or so was largely driven by a somewhat more hawkish tone from key central bankers:

- Fed Chair Janet Yellen is really continuing to reiterate that it’s appropriate to raise interest rates gradually. Nothing new there but comments by Yellen and other Fed officials referring to strength in share markets indicate that they don’t see share markets as a constraint to raising rates again.

- More importantly, ECB President Draghi noted that “the threat of deflation is gone and reflationary forces are at play” and "political winds are becoming tailwinds" (presumably a reference to President Macron's pro-reform and pro-Europe election victory in France, in particular) and that monetary policy will need to adjust once inflation rises.

- Bank of England Governor Mark Carney indicated that “some removal of monetary stimulus is likely to become necessary” if risks continue to diminish.

- Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz repeated that rate cuts have done their job and that “we need to be at least considering that whole situation [low interest rates] now that the excess capacity is being used up”.

The last three basically signalled that thought is being given to an exit from ultra easy monetary policy. In the face of such seemingly synchronised comments, it’s little wonder bond yields rose. Perhaps the most significant was the shift in tone by Mario Draghi – with overtones of former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke’s indication in mid-2013 that the Fed will start phasing down (or tapering) its quantitative easing (bond buying) program. This saw bond yields back up and shares fall around 8% and became known as the “taper tantrum”. So maybe the current episode is “taper tantrum 2.0”.

Bonds and shares are a bit vulnerable to a correction

The rally in bonds this year had arguably gone a bit too far and positioning had become excessively long and complacent leaving them vulnerable to a rebound in yield that we are now seeing. Similarly, we have been concerned for some time that global shares are vulnerable to a correction given solid gains in most markets for the year to date and high levels of short-term investor optimism and complacency on some measures. As we have seen over the last week, worries about central bank tightening have provided a potential trigger. And this could have further to go if bond yields continue to back up sharply.

Three reasons not to be too fussed

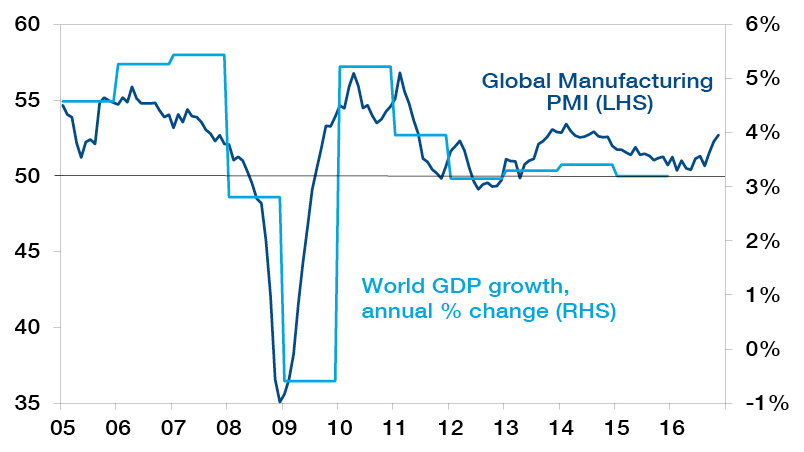

However, there are several reasons not to be too concerned. First, the shift in the tone of central bank commentary just matches the improvement seen in global growth and the receding risks of deflation, so it is actually good news. Global business conditions indicators (or PMIs) are strong (next chart), the OECD’s leading economic indicators have turned up, jobs markets have tightened and global trade is up.

Global business conditions PMIs are solid

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

In particular, Eurozone economic confidence readings – both for consumers and business – are strong and at their highest in nearly a decade (see the next chart). So it makes sense for Mario Draghi to sound a bit more upbeat. If growth relapses, easy money exit talk will pause or fade too – much as we have seen in the US at various points over the last four years.

Eurozone economic confidence and GDP growth

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

Second, with underlying inflationary pressures remaining weak, monetary tightening is likely to remain very gradual. There are two main forces serving to keep inflation down:

- Because of years of below-trend growth globally, spare capacity remains and this will constrain core inflation. While headline inflation bounced over the last year, this was largely due to the bounce in energy prices, which has not been sustained, whereas core inflation remains very subdued (at 1.4% year on year in the US, 1.1% in the Eurozone and zero in Japan). This partly reflects continuing spare capacity, which limits pricing power. As can be seen in the chart below whenever the capacity utilisation measure is around zero or below inflation tends to fall or remain soft. Of course this is a cyclical factor that will eventually fade.

Low capacity utilisation still keeping a lid on underlying inflation pressure

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

- At the same time structural factors continue to bear down on inflationincluding technological innovation – eg, artificial intelligence and robots hollowing out the middle class and along with a rising services sector weighing on wages growth, Amazon reaping havoc on retailer margins in the US and potentially soon too in Australia, and Verizon in the US moving to unlimited mobile data plans (won’t this kill the need for the NBN for most households?).

- As a result of these cyclical and structural factors, corporate pricing power and wages growth remains weak just about everywhere. The lack of significant inflation pressure will keep central banks gradual as we have seen with the Fed over the last four years since the taper tantrum of 2013:

- The Fed – while Janet Yellen does not appear to be too concerned about inflation running below target (its currently 1.4% against the Fed’s 2% target) because she believes that the tight US labour market will eventually drive higher wages growth and inflation, others at the Fed have expressed concern about the inflation undershoot and so a slowing in Fed rate hikes is possible (eg, no hike in September, hike in December). There is certainly nothing in what Yellen has said pointing to a faster tightening.

- The ECB – Mario Draghi is right to warn policy will need to adjust once inflation rises. But at this stage there is little evidence of much tick up in underlying inflation in Europe. The total of unemployment and underemployment in the Eurozone at 18.5% is about 4 percentage points above where it was prior to the GFC acting as a huge constraint on wages growth. And political risk around Italy will slow Draghi from moving too quickly. Our view remains that the ECB will announce a slowing (or taper) in its quantitative easing program later this year (from €60bn a month to maybe €30bn a month for 2018) but that rate hikes are a way off.

- The Bank of Japan – with inflation stuck at zero and the BoJ committing last September to continuing quantitative easing and a zero 10 year bond yield until inflation rises above 2%, it’s likely years from any exit from easy money.

- RBA – while the drag from plunging mining investment is fading and the RBA remains upbeat, soft consumer spending, slowing housing investment, high underemployment and record low wages growth are likely to prevent a rate hike for at least a year or more. So we have seen no hawkish tilt from the RBA.

Finally, even though global monetary policy has gradually tightened thanks to four Fed hikes over the last two years, it’s a very long way from tight levels that will bring the bull market in shares to an end. As such – barring an exogenous shock – this global growth cycle and bull market in shares will likely remain long and drawn out.

Implications for investors

At the time of the 2013 taper tantrum, there was much fear that an end to US money printing would lead to a major bear market, send bond yields sharply higher (as one source of bond buying dried up) and imperil the US and global economy. In the end it was a bit of a non-event as shares resumed their uptrend and the global economy continued to recover. The same is likely to be the case with the latest taper tantrum:

- With inflationary pressures remaining weak and monetary tightening likely to remain gradual (and non-existent in many countries including Australia for some time) the uptrend in bond yields is likely to remain gradual too.

- While shares remain vulnerable to a short-term correction (on easy money exit talk), with monetary tightening likely to remain gradual and dependent on a further improvement in growth it’s unlikely to become tight enough to cause a major bear market in shares any time soon.

- The search for yield will likely continue but may fade in intensity as bond yields gradually rise. This probably means that, while listed bond proxies such as global real estate trusts and listed infrastructure may be constrained as they were initial beneficiaries of the search for yield, unlisted property and infrastructure have further to go.

Exiting from ultra easy money not the end of the world

Finally, for those who say that central banks can never exit money printing and zero interest rates – just look at the US! Over the last four years, the Fed has phased down and stopped money printing or bond buying, raised interest rates four times and announced that it will start allowing its bond holdings to run down by phasing down the rolling over of maturing bonds in its portfolio. Each of these moves have caused uncertainty but have not crashed the US bond market, shares or the economy. Other central banks are likely to follow the Fed model.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital

|