Not only are we further down the path of defined contribution (DC) provision than any other major pension market, but our system is lauded as one of the most advanced in the world.

As Robin Bowerman, Principal, Market Strategy & Communications at Vanguard Australia, observes in a recent Smart Investing article, a recent survey ranked Australia as the world's second best country for a comfortable retirement-behind only our neighbours in New Zealand.

So developments here are often seen as a bellwether for other markets as they move further down the DC path and grapple with the challenges of moving pension liabilities off corporate and government balance sheets and placing more responsibility on the shoulders of individuals.

But let’s not get too complacent. Australia's retirement system definitely has some great attributes, but is it leading to satisfactory outcomes for all retirees?

The unhappy country

The transition to retirement generally brings increased contentment with uncertainty giving way to acceptance, as you can read in this great piece by my colleague in the US Anna Madamba.

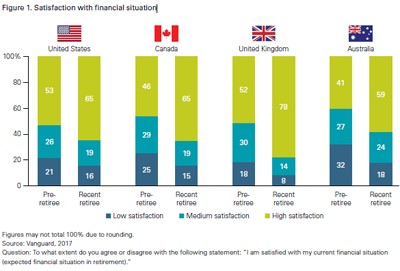

And while this is as true for Australians as it is for American, British and Canadian retirees, the level of local respondents reporting high satisfaction is the lowest of the four countries surveyed in Vanguard's recent paper, Retirement transitions in four countries – as you can see in the graph below.

So why are we so relatively unhappy here in Australia? I'd like to look at the part that choice plays in influencing outcomes.

DC models like ours transfer the primary responsibility for retirement from the government and the employer to the individual. This naturally generates a number of choices for retirees.

- How much should I take as a lump sum and how much as an income stream?

- Should I think about an account-based pension or an annuity...or a combination of both?

- How do I manage my retirement income to maximise my government entitlements?

Compared with some overseas retirement regimes, our combination of compulsory superannuation, means-tested age pension and relatively complex drawdown requirements requires a higher degree of financial literacy and dependence on professional advice.

And while most of us would support the principle of encouraging deeper engagement, in practice the need to choose between more complex options may be leading to dissatisfaction.

Too many flavours?

Behavioural scientists have shown that increased choice does not necessarily lead to increased happiness.

The famous Jam Study demonstrated that the more options we have, the harder it is to make a decision. Faced with more flavours of jam, consumers buy fewer jars. For some this can end in choice paralysis. For others it can lead to the well-documented phenomenon of buyer's remorse as they look back with regret at the jam flavours they didn't buy.

It's the same with super.

- What if I'd taken more advantage of super's concessional tax framework by putting more before-tax contributions into my super while I was working?

- What if I'd put my super into a lower-cost fund that charged less for a similar outcome?

- What if I'd changed my growth/defensive asset mix before making the transition to retirement?

Cutting a path ahead

As an industry we need to cut through the tyranny of choice overload and make sense of retirement planning. We can do this in two main ways.

From a mass customised ‘default’ perspective, product manufacturers can move towards adopting the incoming CIPR (Comprehensive Income Products for Retirement) architecture that will help to develop clearer pathways to retirement.

And from a bespoke advice perspective, financial advisers can play a crucial role in helping clients make sense of the choices and guide them to a satisfactory outcome in retirement.

Based on: Retirement transitions in four countries, January 2017, Anna Madamba, PhD, and Stephen P. Utkus

Paul Murphy

07 July 2017

www.vanguard.com.au

|