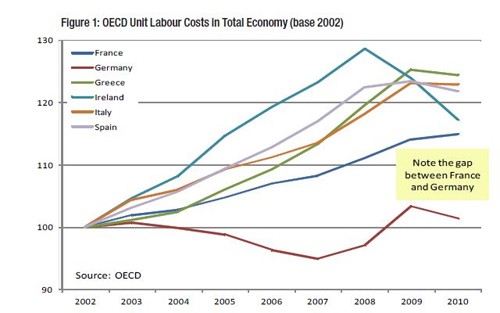

Following the stagflation of the 1970s, the world entered an extended period of growth driven by host of genuine benign innovations. This environment enabled an extended period of leverage and excessive indebtedness by many individuals, corporations and governments. This came to a crashing halt in 2007-2008. We are now several years into what is almost certainly an extended period of deleveraging. The euro mess Initially many Europeans felt the global financial crisis would be contained to the US subprime market, but what quickly became evident was that many European banks held huge portfolios of securitised debt. Like the Americans, their governments needed to bail out large financial institutions that were too big to fail. However, countries in the eurozone have an additional impediment to deleveraging: they do not have the safety valve of their own free-floating currencies. Instead they signed up to a single currency, thereby forgoing the natural balancing mechanism that the foreign exchange markets afford. From day one, the euro was known to be economically illogical. Something has to give if you have (a) different nations with sovereignty over their fiscal arrangements, (b) limited practical mobility of labour (for cultural and language reasons), and (c) no institutionalised, federally directed transfers of wealth. But these economic realities were trumped by politics aimed at bringing the nations together in a close union to promote trade and peace. As we now know, joining the eurozone was a boon for the peripheral countries (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain or PIIGS) as they were able to piggyback on the aggregate strength of the eurozone with more or less one interest rate applied to the sovereign debt of each of its countries. Many bondholders thought sovereign default would never eventuate and that, as the only other mechanism for different risk outcomes (that is, currency) had been removed, the same interest rate should apply to all eurozone sovereigns. They could not have been more wrong. For instance, the private holders of Greek sovereign bonds are being cajoled into accepting a 50 per-cent (or worse) "voluntary" haircut. They may well have to agree to or face a worse outcome. And, even then, Greece will probably still be insolvent. Greece is smaller than its fellow PIIGS. Ireland will probably renegotiate the bailout that was forced on it last year. Italy and Spain have huge deficits that are impossible to service with the higher interest rates being forced on them. And France, one of the heavyweights in the eurozone, also has large fiscal deficits, huge unfunded healthcare and pension liabilities, and a political environment that may make serious labour and pension reform impossible. Moreover, during the last decade its labour costs have escalated in comparison to Germany's (see Figure below). Mixed progress on deleveraging So where are we now? Joe and Judy (the Gen X family described in the previous installment) can no longer use their home as an ATM. They have started to save. Indeed, in much of the developed-world private households in aggregate have become net savers. Much of this is due to belt tightening, forced by removal of access to consumer credit and real or perceived employment instability. The downside to thrift is the hit to gross domestic product (GDP) caused by lower consumption. This is why most governments around the world have run budget deficits for at least four years, causing government balance sheets to blow out. Statistics from the McKinsey Global Institute track key nations' debt levels. Clearly some countries, such as Japan and the UK, have massive levels of debt, which is an enduring challenge for those nations. France and Spain also have high and growing debt and have not yet started to deleverage. In the US, however, deleveraging is becoming evident in the numbers. This is mainly due to the private debt destruction mentioned earlier. McKinsey Global Institute believes that US households may be about half way through the deleveraging process. This does not take the US out of the woods, as government debt, including that of many near-bankrupt states, continues to grow. Moreover, the US government has massive unfunded liabilities relating to its social contract with its citizens. These are not in the form of contractual bond obligations, but include programs such as Social Security and Medicare. The trustees of those programs estimate the unfunded liability to be US$59 trillion. By adding other unfunded liabilities, such as pension obligations for government employees, some have estimated this number at $200 trillion. However, it seems obvious that much of this unfunded liability will evaporate before the cash starts haemorrhaging from government coffers. If something cannot happen, it won't. The US government will renege on its social contract and its citizens will accept massive changes to entitlements and work longer. It will be ugly, but if any country can wrangle this change, it will be the US. It may take some years before the US consumer becomes the driver of growth and we may see a series of recessions beforehand, but I am not betting against the US in the longer term. As Winston Churchill put it: "You can always count on Americans to do the right thing - after they've tried everything else". On the other hand, I find it difficult to see how many countries of the eurozone can rebound while the constraints of a single currency remain in force. The politics of the euro are so strong that it will probably be around for a while. At best, this just means that it will take that much longer before those nations are able to recover, but we could well see a more violent form of solution as citizens of PIIGS reject the austerity and loss of sovereignty that comes with staying in the euro.

China and Australia China is one of the most significant drivers of economic prosperity for Australia. The issue with China is not its own process of deleveraging, but its reliance on exports to countries that are. Europe is China's biggest export market. This will be a problem for China if Europe's fortunes turn soggy. Some people think that in a rapidly developing economy such as China's, the key enabler is the mobilisation of capital and labour. The impact of inefficient allocation of capital (such as empty apartments) can be quickly cleared. Others believe that China will be able to engineer a soft landing as inflation is easing and looser monetary policy can be pursued. Australia is leveraged to China's fortunes and our own housing market continues to defy the gravity experienced by most other developed countries. These two risks are not independent and I suggest that too much Australian home-country bias may not be wise. At least the Australian dollar can act as a safety valve to make our exports more competitive and attractive. The way forward for investors Even if the eurozone manages to stave off default and dismemberment for a year or so, the effect would still be a downturn, although risky assets may rally with relief. In my view, this just puts off reform and adjustment. Just because the awful is unthinkable does not make it less likely. A messy disintegration of the eurozone will see deep depressions in some countries and massive economic and social disruption that will have worldwide effects. This would be very difficult for risky assets. Either way, much of the developed world will experience poor growth over the coming years, if not experience a series of recessions or worse. A gloomy forecast indeed. However, investing is about buying risky future cash-flow streams at the right price. Arguably, much of this gloom is already factored into asset prices. This is why I believe it is critical to engage investment managers that have the skill and mandate to select assets that are likely to give a good reward for risk. And this can change rapidly as the prices of individual assets move. By: Chris Condon

30th April 2012

Source: Investment Magazine http://investmentmagazine.com.au

|